If you aren’t familiar with Hermann Minkowski, it was his notion of space (the Minkowsiki space) in which Einstein’s theory of relativity was formulated. In this mathematical space setting the three ordinary dimensions of space are combined with the one dimension of time in order to form a four-dimensional manifold for representing spacetime.

Too difficult to understand? Ask your local physicist to help you out there because I have to admit, I can’t…

At the start of the comic, however, the author does give you an inkling of what he wants to explore about Minkowski Space. When the protagonist, Randall, walks into his classroom, his professor explains, “…and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality. As said by one of Albert Einstein’s teachers.”

What to Expect

Being that the comic seems to be one of alternate realities—where Randall finds himself daydreaming of this whole other world called Arcadia, a daydream that almost seems too real to ignore—it seems apt that this little bit explained by the teacher will prove to be vital to the rest of the story.

The main conflict in the story seems to focus on the myth of the giant bird, the Minokawa that devours entire planets and moons because it likes how they look.

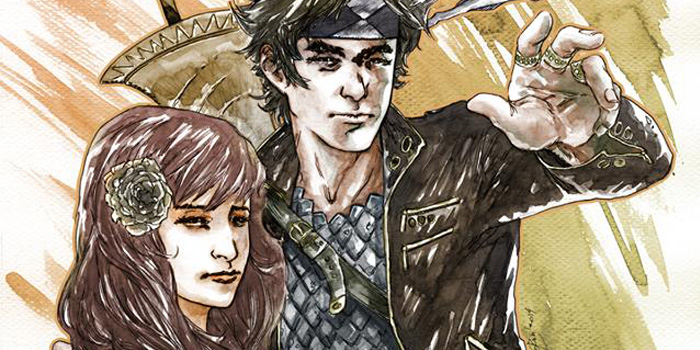

I picked up this comic mainly because of the art style. Just like in Manila Accounts 1081, Felizmenio’s water-color style is gorgeous to look at—as long as you’re able to understand what’s going on. The great thing about this comic however—compared to Manila Accounts 1081—is that the color makes the all the figures and elements in each panel much clearer.

Overall, I’d say that the ideas in the book are pretty interesting. But as a reader, I wasn’t entirely invested in the comic. Here’s why…

The Breakdown

Characterization is an important factor in every story. Creating memorable characters, however, needs more than just a name and a background. In the case of Minkowski Space Opera, I couldn’t relate to the character at all.

Who is this guy? What is he like? We hardly get to know anything about the character throughout the entire comic, just that he’s a regular daydreamer, has constant headaches, and tries to act cool all the time.

In the book Save the Cat, Blake Snyder says something that I believe is true of a lot of stories these days:

“I don’t like the Lara Croft character. Why would I? She’s cold and humorless. And while that’s fine in the solitary world of video games and comics, it doesn’t make me want to leave my home to go see the movie. The people who produced this film think they can get you to like her by making her ‘cool.’ This is what amounts to ‘character development’ in au currant movies: ‘She drives a cool car.’ That’s someone’s idea of how to create a winning hero.

“Well, folk, I don’t care about how ‘cool’ it is, this isn’t going to work.”

Good characterization isn’t about how cool a character is. Good characterization is about how human that character is. If the reader isn’t able to see a character as a human being, then the author or creator has lost that connection with his readers.

Again, Blake Snyder: “…liking the person we go on a journey with is the single most important element in drawing us into the story.”

Why is it important for the reader to connect with a story’s characters? The Golden Theme puts it perfectly: “Letting people know they are not alone in their suffering is one of the primary responsibilities of a storyteller.”

In Minkowski Space Opera there’s nothing about the characters that stand out. They all sound the same. Nothing distinguishes one from the other. In certain instances they even finish each other’s sentences because they don’t have specific voices. They only have one voice: the author’s. This makes it difficult for me, as a reader, to really immerse myself in this world—no matter how fantastic it is.

Blake Snyder suggests that movies today lack what he calls the “Save the Cat” scene. “It’s the scene where we meet the hero and the hero does something—like saving a cat—that defines who he is and makes us, the audience, like him.”

Randall has no such defining moment throughout the story. As far as we know, he’s just a lazy guy wasting his time in school. Sure, many of can relate to that, but that doesn’t necessarily make us like him.

The first most important step a creator has to do about his or her characters, is make the audience like them. If the audience isn’t made to care about your character, what makes you think they’ll stick around to know more about them?

Personally, I felt that the flashbacks were misplaced in this comic book. The first pages of a comic should be spent in getting the reader invested in the story.

To have a flashback within a dream just seemed to deter the story’s pace even more. It became difficult to follow, primarily because I, as a reader, knew nothing about this world. The whole history of Aeon and Arcadia might have been more interesting if it either came later on in the story, or at the very start.

That’s how the Fellowship of the Ring handled the whole history of Middle Earth. It introduced the world, and the whole theme and mission of the fellowship by relating Middle Earth’s past.

Serenity also did a pretty good job, in my opinion, of explaining its own world by zooming out from this montage of historical events to reveal a classroom—where River is quietly listening—being lectured by its teacher on the universe’s history. This classroom setting then shifts and we realize that it’s all a dream induced by the people experimenting on her brain.

If look at The Incredibles on the other hand, they took that “Save the Cat” scene to heart and made you like Mr. Incredible straight away before they began introducing you to the world that the story takes place in. Even the way that this world is introduced is interesting—wherein it’s played out like a documentary feature talking about how society began to reject superheroes.

Even Wall-E did an incredible job of introducing its world’s history without making it seem too boring and complicated. By having Wall-E walk around the city alone, you get a complete picture of what brought about the demise of the human race on earth. Wall-E runs over a newspaper headline. He walks past billboards and video ads that showcase bits and pieces of history.

The last thing you want your readers to think is, “What the hell is going on here?” Because that could easily be the point at which they put down the comic book without bothering to read the rest. When that happens, it doesn’t matter how good your climax and ending are, you’d have already lost a reader.

To have Randall and Artus read through the Ballad of Aeon where all we really see is action panels one after the other just isn’t as compelling enough. I used to think that big action equals big audience reactions. Hence I myself was a victim of writing a lot of explosions and gun fights, etc. But the truth of the matter is that action doesn’t equal audience empathy.

And while there are those that love huge explosions, and love watching things blow up, sometimes if the stakes aren’t high enough, and the audience isn’t invested enough, those pyrotechnics just don’t add up (think Michael Bay’s Transformers movies).

The myth of the Minokawa, on the other hand, is one part of the story that I believe should have come first. If it had at least come before the Ballad of Aeon, things would have made more sense. As it is, you just feel confused at the start, and then put things together after your confusion.

But what if you, as a reader, were too confused and baffled to continue reading? What if you stopped before arriving at the story of the Minokawa? You’d never have gotten it, then. That’s why good plotting is important. You want to be able to make sense quickly enough that before your readers have a chance of bailing, they’ll know just what it is your story is about.

If you were to submit a story to a traditional publisher, they’d only read the first few pages of your book. So it’s important to make sure that those first few pages count.

Think about when you meet someone for the first time. More often than not, the person you eventually end up with is someone with whom you’ve connected with at the very start, not someone who simply seemed cool and interesting.

Like people, a story’s first job is to make its readers fall absolutely in love with it.

Conclusion

Overall, I love the artwork, I love the panels. They’re the saving grace that made me keep reading this comic, because Felizmenio’s work is simply gorgeous.

But all that beauty and elegance falls flat if I can’t be made to care for the actual characters in the book. Always give the readers a reason to follow your characters.

I’d follow Frodo because I can see that he’s good-natured and courageous despite his size. I’d follow Wall-E because his curiosity is just so damn adorable. I’d even follow Yagami Light because despite his treacherous ways, he’s a character that easy to relate to and empathize with. He’s human despite his flaws.

There’s a lot of thought and philosophy put into this comic book, and it has great potential for having so. But in terms of getting me, as a reader, to become fully invested in its story, it needs some work.

Share with us your thoughts on this Filipino Komik, and what impressions it made on you. Leave your thoughts in the comments.

1. What did you think of Randall as a character?

2. What was your reaction to the Minakawa myth?

3. Which parts had you at the edge of your seat?

4. What would you have changed about the story, if you had the chance?

5. What did you think of the art?

Visit the Minkowski Space Opera Facebook Page

Visit the Frances Luna III’s Facebook Page

Visit Aaron Felizmenio’s DeviantArt Page